|

|

- Search

| Korean J Art Hist > Volume 307; 2020 > Article |

|

Abstract

Notes

1) The textual source of the uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī is the Sutra of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī (Foding zunsheng tuoluoni jing 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經). The sutra was so popular that it was translated five times in China, once each by Buddhapālita (T. 19, no. 967), Du Xingyi (T. 19, no. 968), and Yijing (T. 19, no. 971), and twice by Divākara (T. 19, no. 969, and T. 19, no. 970). They have similar but slightly different contents. Among these, the translation by Buddhapālita was most widely used. For the political characteristics of the preface of Buddhapālita’s translation, see Antonino Forte, “The Preface to the So-called Buddhapālita Chinese Version of the Buddhosṇīṇa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra” unpublished paper, quoted in Paul F. Copp, “Voice, Dust, Shadow, Stone: The Makings of Spells in Medieval Chinese Buddhism,” PhD dissertation (Princeton University, 2005), 46, footnote 78; Chen Jinhua, “Śarīra and Scepter: Empress Wu’s Political Use of Buddhist Relics,” Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 25, no. 1-2. (2003): 33-150; and T. H. Barrett, “Stūpa, Sūtra, and Sarīra in China, c. 656-706,” Buddhist Studies Review 18, no. l (2001): 1-64. Barrett also discussed the role of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī in developing print technology in China.

2) As for the dhāraṇī pillar, see Paul F. Copp, The Body Incantatory: Spells and the Ritual Imagination in Medieval Chinese Buddhism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 141-196; Liu Shufen 劉淑芬, “Jingchuang zhi xingzhi, xingzhi he laiyuan: jingchuang yanjiu zhi er” 經幢的形制、性質和來源 經幢研究之二, Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo jikan 中央研究院歷史語言研究所集刊 68, no. 3 (1997); Liu Shufen 劉淑芬, Miezui yu duwang: Foding zunsheng tuoluoni jingchuang zhi yanjiu 滅罪與度亡: 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經幢之研究 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2008).

3) After the Tang dynasty, the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī as well as various dhāraṇī were inscribed on the dhāraṇī pillar. As for the dhāraṇī pillars from the Liao and Jin dynasties, see Zhang Mingwu 張明悟, Liao Jin jingchuang yanjiu辽金经幢研究 (Beijing: Zhongguo kexue jishu chubanshe, 2013).

5) As for the Great Master Xuanyan (also known as the monk Yungui 蘊珪), and his supervision of Chaoyang North Pagoda’s construction, see Youn-mi Kim, “The Hidden Link: Tracing Liao Buddhism in Shingon Ritual,” Journal of Song-Yuan Studies 43, Special Issue on the Liao Dynasty (2013 [published in 2015]): 15-161.

6) For the excavation report, see Liaoning-sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 遼寧省文物考古硏究所 and Chaoyang shi Beita bowuguan 朝陽市北塔博物館 eds., Chaoyang Beita: Kaogu fajue yu weixiu gongcheng baogao 朝陽北塔: 考古發掘與維修工程報告 (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 2007).

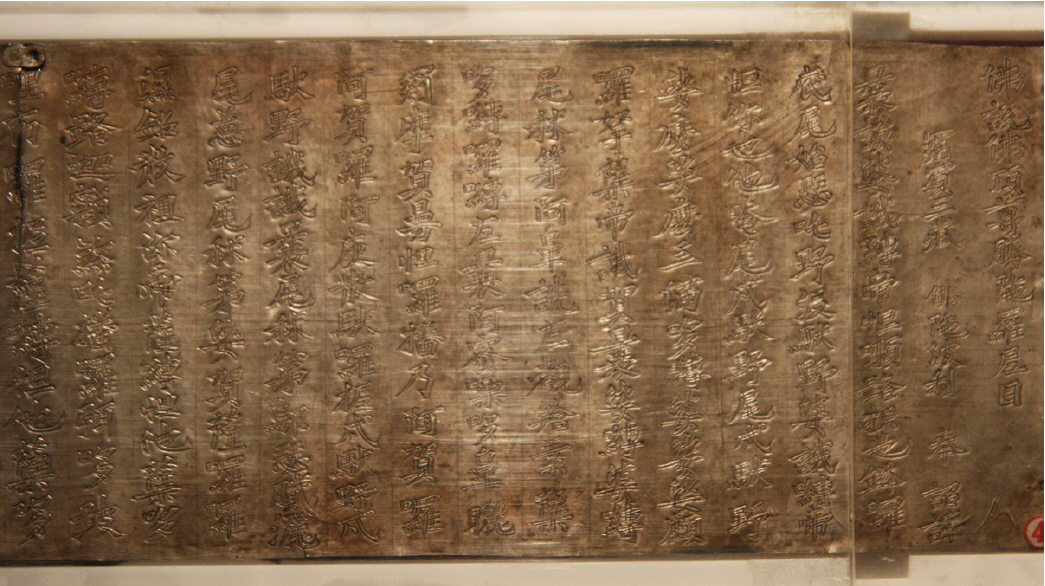

7) A stone stele placed before the relic depository records the most important objects enshrined in the depository. The list includes the term jingta, which refers to this metal miniature pagoda that encased a long roll of silver plate engraved with Buddhist dhāraṇīs. The sutras found within this miniature pagoda were mainly Buddhist incantations.

8) The main wall of the relic depository, from which the gold mandala was excavated, was engraved with the same type of mandala, but rotated 45º clockwise. For an image of this mandala on the wall, see Liaoning-sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Chaoyang shi Beita bowuguan eds., Chaoyang Beita, fig. 21-2.

10) For a list of these scriptures, see Yang Hijŏng (Yang Heejung) 양희정, “Han’guk p’altae posal tosang yŏn’gu” 韓國 八大菩薩圖像 硏究 , M.A. thesis (Seoul National University, 2006), 5-9. For a detailed analysis of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas in Liao Buddhism and Buddhist art, see Sŏng Sŏyŏng 成敘永. “Liao dai bada pusa zaoxiang yanjiu” 遼代八大菩薩造像研究, Liao Jin lishi yu kaogu 遼金曆史與考古7, no. 1 (2017): 81-109.

11) Kim, “The Hidden Link,” 125-130; Foding zunsheng tuoluoni niansong yigui fa 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼念誦儀軌法, T. 19, no. 972; and Bada pusa mantuoluo jing 八大菩薩曼茶羅經, T. 20, no. 1167: 675b.

12) Foding zunsheng tuoluoni niansong yigui fa, T. 19, no. 972: 364b-c. For a further comparison of Chaoyang North Pagoda mandalas and the ritual manual, see Kim, “The Hidden Link,” 122-130.

15) Youn-mi Kim, “Eternal Ritual in an Infinite Cosmos: The Chaoyang North Pagoda (1043-1044),” PhD Dissertation (Harvard University, 2010), 123-124.

17) For the Eight Great Bodhisattvas appearing in the mandalas from Dunhuang, see Michelle C. Wang, The Visual Culture of Esoteric Buddhism at Dunhuang (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018).

18) Yang Hŭi-jŏng (Yang Heejung) 양희정, “Koryŏ sidae Amit’a p’altae posalto tosang yŏn’gu” 고려시대 아미타팔대보살도 도상 연구, Misul sahak yŏn’gu 美術史學硏究 257 (2008): 78.

19) It is probably because the Great Master Xuanyan, who supervised the construction of Chaoyang North Pagoda, also supervised the production of the mandala.

20) There is no clear boundary between mantra and dhāraṇī, although the former is usually shorter. For more on mantra, see Ryūichi Abe, The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse (Columbia University Press, 1999), 5-6, 12-13, 262-264.

21) Every Buddha has the same thirty-two sacred bodily marks (三十二相), which include white tufts of shining hair between the eyebrows (Sk. ūrṇā) and a protuberance on the crown (Sk. uṣṇīṣa).

22) This part of the sutra has an obvious mistake, in that the position of this bodhisattva overlaps w ith that of Sarvanivaraṇaviṣkambhin bodhisattva, who is also described as being seated in front of the Buddha. Since the sutra describes the bodhisattvas in a clockwise manner, starting with Avalokiteśvara bodhisattva, Kṣitigarbha bodhisattva should be on the right of Sarvanivaraṇaviṣkambhin bodhisattva. Many of the surviving Eight Great Bodhisattvas Mandalas place Kṣitigarbha bodhisattva on the right of Sarvanivaraṇaviṣkambhin bodhisattva.

23) Bada pusa mantuoluo jing, T. 20, no. 1167: 675b-c. English translation by the author. The names and attributes of the bodhisattvas are marked in bold by the author.

24) For a comparison of Chaoyang North Pagoda mandalas and the ritual manual, see Kim, “The Hidden Link,” 128-130.

26) Kim, “Eternal Ritual in an Infinite Cosmos,” 124-127. For more on the Eight Great Bodhisattvas and Mandalas of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas produced in India, see Pratapaditya Pal, “A Note on the Mandala of the Eight Bodhisattvas”, Archives of Asian Art 26. (1972-1973): 71-73; Nancy Hock, “Buddhist Ideology and the Sculpture of Ratnagiri, Seventh through Thirteenth Centuries,” PhD Dissertation (University of California-Berkeley, 2005); Radha Banerjee, Ashtamahabodhisattva: The Eight Great Bodhisattvas in Art and Literature (New Delhi: Abha Prakashan, 1994); Bimal Bandyopadhyay, Buddhist Centres of Orissa: Lalitagiri, Ratnagiri, and Udayagiri (New Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan, 2004); Matsunaga Keiji 松長恵史, Indoneshia no Mikkyō インドネシアの密教 (Kyōto: Hōzōkan, 1999), 64-103; Geri Hockfield Malandra, Unfolding a Mandala: The Buddhist Cave Temples at Ellora (New York: State University of New York Press, 1993). For more on the Eight Great Bodhisattvas in Korea, see Mun Myŏngdae 문명대, “Noyŏng ŭi Amit’a Chijang purhwa e taehan kochal” 노영의 아미타 지장불화에 대한 고찰, Misul charyo 미술자료 25 (1979); 47-57; Chŏng, Ut’aek (Chung Woo-thak) 정우택, Kōrai jidai Amida gazō no kenkyū 高麗時代阿弥陀画像の研究 (Kyōto: Nagata bunshōdō, 1990), 133-183; Yang, “Han’guk p’altae posal tosang yŏn’gu”; Yang, “Koryŏ sidae Amit’a p’altae posalto tosang yŏn’gu”; and Ku Chin-gyŏng 구진경, “Koryǒ Chosŏn sidae Amit’a p’altae posalto ǔi pigyo yŏn’gu” 고려 조선시대 아미타 팔대보살도 비교 연구, M.A. thesis (Dongguk University, 2004).

28) Lü Jianfu 呂建福, Zhongguo mijiao shi 中國密教史 (Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, 2011), 470-417.

29) For example, see Yu Bo 于博, “You bada lingta tuxiang guankui Liao dai fojiao xinyang” 由八大靈塔圖像管窺遼代佛教信仰 Dongbei shidi 東北史地 no. 5 (2015): 30; Luo Zhao 羅炤, “Yingxian muta suxiang de zongjiao chongbai tixi” 應縣木塔塑像的宗教崇拜體系, Yishu-shi yanjiu 藝術史研究 12 (2010): 198-203; Sŏng, “Liao dai bada pusa zaoxiang yanjiu,” 84; and Wei-Cheng Lin, “Performing Center in a Vertical Rise: Multilevel Pagodas in China’s Middle Period,” Ars Orientalis 46 (2016): 115.

30) Li Jingjie 李靜傑, “Shanbei Song Jin shiku Dari rulai tuxiang leixing fenxi” 陝北宋金石窟大日如來圖像類型分析, Gugong bowuyuan yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 167, no. 3 (2013): 127. Li does not specify whether the “four offerings bodhisattvas” are the four inner offerings bodhisattvas (nei gongyang pusa 內供養菩薩) or the four outer offerings bodhisattvas (wai gongyang pusa 外供養菩薩) from the Diamond World Mandala.

31) Chen Mingda 陳明達, Yingxian muta 應縣木塔 (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 1966).

33) In photographs, only the right arm of Mañjuśrī in the southwest and the left arm of Vajrapāṇi in the west appear to have been destroyed; their original positions are unrecognizable.

34) 14C10 × (1/2)^10 × (1/2)^4 = 0.0610961914. I am thankful to Joon Soo Ryu, the COO of Bitsensing, for kindly calculating this probability.

35) As for the construction date of Daming Pagoda, I follow the opinion of Fujiwara Takato 藤原 崇, who suggested that the old inscription, “Shouchang sinian” 壽昌四年, discovered inside the pagoda in 1983, is the pagoda’s construction year. Fujiwara Takato,Kŏran pulgyosa yŏn’gu 거란 불교사 연구 (Seoul: Ssiaial, 2020), 266, 288-293.

36) For more about this mandala, see Fujiwara Takato, Kŏran pulgyosa yŏn’gu, 269-288; and Sŏng, “Liao dai bada pusa zaoxiang yanjiu”, 85. Fujiwara and Sŏng analyze the mandala as one type of Eight Great Bodhisattvas Mandala.

37) My photograph of Daming Pagoda’s north wall lacks the resolution needed to confirm the attributes. So I referred to the chart in Sŏng, “Liao dai bada pusa zaoxiang yanjiu,” p. 94 in order to complete Table 4.

38) Luo Zao also suggested that the fifth story of the pagoda forms a Uṣṇīṣavijayā Mandala, but he did not think this dhāraṇī impacted the design of the pagoda’s other floors. See Luo, “Yingxian muta suxiang de zongjiao chongbi tixi,” 198-201.

40) For more on the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī ritual embodied by Yingxian Timber Pagoda, see my forthcoming article in International Journal of Buddhist Thought and Culture in December 2020.

42) Chen Shushi and Tong Qiang, who had a chance to enter the relic depository of Baitayu Pagoda in 2012, published an in-depth analysis of the inscriptions engraved on the depository’s ceiling and walls. They also examined the patrons of the pagoda. But they did not think that the depository’s ceiling formed a mandala. Chen Shushi 陳術石 and Tong Qiang 佟強, “Xingcheng Baitayuta digong mingke yu Liao dai wanqi fojiao xinyang” 興城白塔峪塔地宮銘刻與遼代晚期佛教信仰, Liao Jin lishi yu kaogu 遼金曆史與考古, no. 4 (2013): 219-242. Sŏng Sŏyŏng examined the ceiling as an example of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas Mandala from Liao, and suggested that Sixiao’s thoughts may have been reflected in the inscriptions in Baitayu Pagoda’s relic depository. However, instead of Huayan and Pure Land Buddhism relfected, in this mandala, Sŏng focuses on the possible relationship between the mandala and the bodhisattva precepts (pusa jie 菩薩戒). Sŏng,“Liao dai bada pusa zaoxiang yanjiu,” 85-86, 97-98, and 102-108.

43) For a transcript of all of the inscriptions, see Chen and and Tong, “Xingcheng Baitayuta digong mingke,” 234-242.

44) These mandalas, also known as shūji mandara 種子曼荼羅, have some degree of similarity to the ceiling mandala of Baitayu mandala.

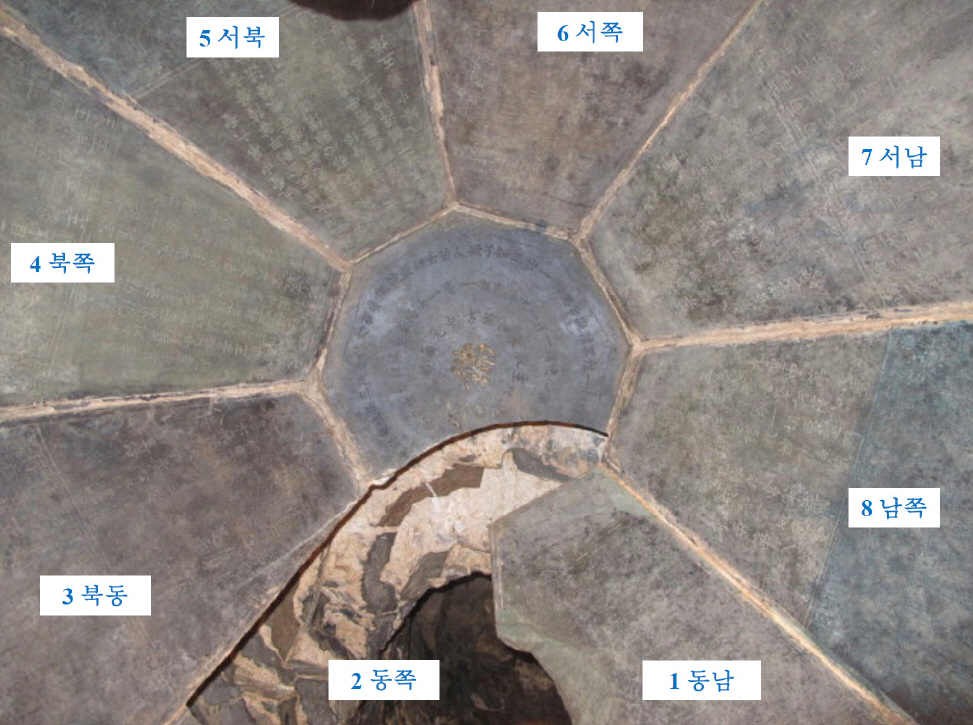

45) Chen Shushi and Tong Qiang wrote that the panels constituting the ceiling are arranged counter-clockwise, but the photograph of the ceiling shows that they are arranged in a clockwise manner. This is because the north and south are overturned when carving on the ceiling as opposed to the ground. See the directions marked in Figure 14 of this paper.

46) 九聖中第二聖 馬頭明王 觀世音菩薩摩訶薩 憐慜眾生如赤子 於一切時施安樂。 。 。 淨飯王宫生處塔。 。 。 八塔中第一塔。 Transcription by Chen Shushi and Tong Qiang. Translation and bolding by the present author. The last six sinographs had been damaged, but Chen and Tong inferred the lost sinographs based on the same pattern being repeated in the other trapezoidal panels.

47) The entire inscription of the second ring reads 曼荼偈云 一毫一相充法界一行一德遍心源清淨廣大喻芳池能療眾生煩惱渴. It came from the scripture Hymn of One Hundred and Fifty Eulogy for Buddhas (Yibai wushi zan fo song 一百五十讚佛頌, T. 32, no. 1680:762a9-10) translated by Yijing義淨 (635-713). Chen and Tong, “Xingcheng Baitayuta digong mingke,” 241n162.

49) The relic depository’s overall relationship with the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī ritual will be discussed in a separate paper I am preparing.

50) Chen and Tong, “Xingcheng Baitayuta digong mingke,” 230-231. For a relevant passage in the sutra, see 大妙金剛大甘露軍拏利焰鬘熾盛佛頂經 Damiao jingang daganlu junnali yanman chisheng foding jing, T. 19, no. 965: 340c13-341a19.

51) For the Eight Great Spiritual Pagodas in Liao, see Youn-mi Kim, “Virtual Pilgrimage and Virtual Geography: Power of Liao Miniature Pagodas (907-1125),” Religions 8, no. 10 (October, 2017): 1-29; Sŏng Sŏyŏng 成敘永, “Jingangjie mantuluo yu xinde bada lingta xinyang de ronghe: Chaoyangbeita tashen fudiao yanjiu” 金剛界曼荼羅與新的八大靈塔信仰的融合: 朝陽北塔塔身浮雕研究, Gugong bowuyuan yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 190, no. 2 (2017): 96-11; and Chu Kyŏngmi (Joo Kyeongmi) 주경미, “Yodae p’altae yŏngt’ap tosang ŭi yŏn’gu” 遼代 八大靈塔 圖像의 硏究, Chungang Asia yŏn’gu 중앙아시아연구 14 (2009): 141-167.

52) Daming Pagoda in present-day Ningcheng County, Chifeng, in Inner Mongolia shows that these modifications observed in the mandala at Baitayu Pagoda were probably shared throughout Liao in the late eleventh century. Vairocana Buddha, the Eight Great Bodhisattvas, the eight bright kings, and the Eight Great Spiritual Pagodas all intermingle on the exterior of Daming Pagoda through the reliefs and inscriptions adorning the pagoda’s ground story.

53) The inscription replaces the letters hua 華, ying 應, and ji 及 in the scriptures with the characters hua 花, dang 當, and yu 與, respectively; however, this does not change the meaning of the phrases. The two verses come from different versions of the Flower Garland Sutra. For the two verses in their original form, see Dafangguang fo huayan jing, T. 10, no. 279: 102a-b; and T. 9, no. 278: 465c29.

55) For the synthesis of Huayan and Esoteric Buddhism in Liao, see Wakiya Kiken 脇谷撝謙, “Ryō Kin jidai no bukkyō” 遼金時代の佛教, Rokujō gakuhō 六條學報 126 (1912): 31-43; Wakiya Kiken, “Ryō-Kin bukkyō no chūshin” 遼金佛教の中心, Rokujō gakuhō 135 (1913); 2-9; and “Ryō dai no mikkyō” 遼代の密教, Wu jin deng 無盡燈 (1912); Kamata Shigeo 鎌田茂雄, Chūgoku kegon shisō no kenkyū 中國華嚴思想の研究 (Tokyo: Tōkyo daigaku shuppankai, 1965), 604-618; Robert M. Gimello, “Wu-t’ai Shan 五臺山 during the Early Chin Dynasty 金朝: The Testimony of Chu Pien 朱弁,” Zhonghua foxue xuebao 中華佛學學報 7 (1994): 501-612; and Henrik Sørensen, “Esoteric Buddhism under the Liao,” Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia, ed. Charles Orzech, Henrik Sørensen and Richard Payne (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2011), 459-461.

56) For a transcription of the dedicatory inscriptions, see Chen and Tong, “Xingcheng Baitayuta digong mingke,” 234.

57) The character hua 花 in the island’s name actually refers to the character hua 華, which is a character in the name Huayan 華嚴 Buddhism. The two characters were sometimes interchangeable, and the inscriptions in Baitayu Pagoda’s relic depository’s ceiling also use hua 花 instead of hua 華 in writing the title of Flower Garland Sutra (as 大方廣佛花嚴經).

58) For a complete transcription of the dedicatory inscriptions from this relic deposit, see Chen and Tong, “Xingcheng Baitayuta digong mingke,” 234.

59) The last prayer in Baitayu Pagoda’s dedicatory inscription is a more general prayer for monks and thus does not mention particular figures.

60) For a transcription of this stele inscription, see Nan Xiang 南嚮, Liao dai shike wenbian 遼代石刻文編 (Shijiazhuang: Hebei jiaoyu chubanshe, 1995), 451.

61) For a transcription of this dedication inscription, see Chen and Tong, “Xingcheng Baitayuta digong mingke,” 234.

62) Zhu Zifang 朱子方, “Ba Xingcheng Tazigou chutu de liangjian shike” 跋興城塔子溝出土的兩件石刻, Liao Jin Qidan Nüzhen shi yanjiu dongtai 遼金契丹女真史研究動態 no. 2 (1984): 1.

65) Jiupin wangsheng Amituo sanmodi ji tuoluoni jing 九品往生阿彌陀三摩地集陀羅尼經, T.19, no. 933: 79c11-15. It was Chen and Tong who first found the twelve names in this dhāraṇī sutra. Chen and Tong, “Xingcheng Baitayuta digong mingke,” 292-230.

66) For more on this monk, see Kamio Kazuharu 神尾弌春, Kittan Bukkyō bunkashi kō 契丹仏教文化史考 (Dairen shi: Manshū bunka kyōkai, 1937), 39, 198-199; and You Li 尤李, “Liao dai gaoseng Sixiao yu Juehuadao”遼代高僧思孝與覺華島,Zhongyang minzu daxue xuebao: Zhexue shehui kexue ban 中央民族大學學報-哲學社會科學版 39, no. 1 (2012): 47-51.

67) Sŏng, Sŏyŏng also pointed out the importance of this monk in Baitayu Pagoda. Sŏng,“Liao dai bada pusa zaoxiang yanjiu,” 81-109.

68) Chen Shushi and Tong Qiang identified in their 2013 article that “撰百本科制四部疏守司空輔國大師” in the inscription refers to the monk Sixiao. Chen and Tong, “Xingcheng Baitayuta digong mingke,” 221-222.

69) The titles of these texts were recorded in the monk Ŭich’ŏn’s catalogue compiled in Koryŏ. Sinp’yŏn chejong kyojang ch’ongnok, T. 55, no. 2184: 1172c28-29. This catalogue informs us that one more Liao monk named Zhishi 志實 had written a commentary on the same scripture, which testifies to the importance of Sutra of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas Mandala in Liao Buddhism.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 10.

Fig. 11.

Fig. 12.

Fig. 13.

Fig. 14.

Fig. 15.

Fig. 16.

Table 1.

Table 2.

Table 3.

Table 4.

Table 5.

References

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 1 Scopus

- 5,826 View

- 98 Download

- Related articles in Korean J Art Hist